CLEVELAND, OH — At precisely midnight on January 1, 2024, something extraordinarily criminal happened across the State of Ohio. One thousand and eighty-one police officers — men and women from 38 law enforcement agencies entrusted with the power to arrest, search, and use deadly force — ceased to exist as legal peace officers. They became private citizens impersonating law enforcement officers.

Under Ohio law, a police officer’s authority is not a permanent appointment. It operates more like an annual driver’s license. It is a conditional privilege, renewed annually through mandatory training that is reported on computer systems owned by the State of Ohio. When that training isn’t completed by December 31st, the law is unambiguous.

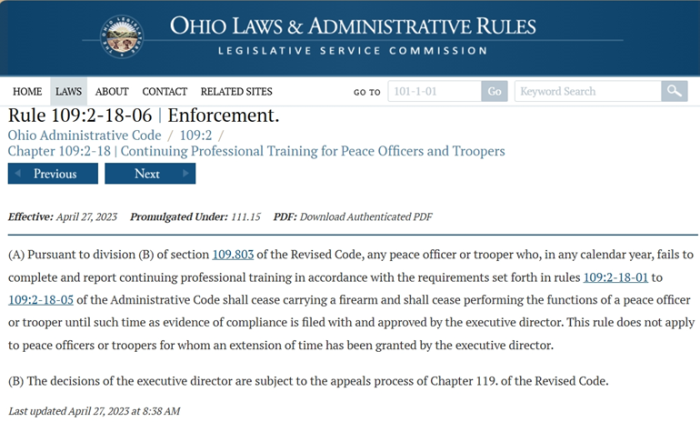

At midnight, the officer’s authority expires. Pursuant to section 109: 2-18-06 of the Ohio Administrative Code, they are to “cease discharging the duties of a law enforcement officer and wearing a weapon.” What remains is a civilian in a state-issued uniform, legally barred from carrying a weapon, making an arrest, or accessing sensitive federal and state criminal records history and law enforcement databases. From a taxpayer’s perspective they are thieves on the city’s payroll creating multi-million-dollar civil liabilities.

Yet according to internal records obtained by EJB News, and testimony from officials within the Ohio Peace Officer Training Academy (OPOTA) during public meetings, these 1,081 private citizen law enforcement impersonators continued to patrol Ohio streets, make arrests, and testify in court throughout January 2024. By month’s end, OPOTA Executive Director Thomas Quinlan had authorized employees to manually override its own computer systems to retroactively validate 310 officers who had spent four weeks performing illegal police work that OPOTA then ‘laundered’ through backdated data entry.

The move shielded police who’d made illegal arrests from being discovered as non-compliant by users of OPOTA’s public database. Sources say an estimated 6000 Ohio peace officers began 2026 in violation of mandatory OPOTA training laws. A police source I spoke to confirmed that Quinlan was again leading OPOTA’s worker to sanitize the training records of non-compliant law enforcers.

Even after Quinlan guided OPOTA workers to launder the records of the 310 “cease function” peace officers, 771 peace officers remained non-compliant, and he provided no notice of their non-compliance to any mayor or appointing authority (civil service commission) who appointed them. He provided no notice to any judge or city or county prosecuting attorney that police they had no knowledge of being private citizens were impersonating law enforcement officers in their cities, villages, townships and counties.

This is not a story about a few bad apples or isolated administrative failures. It is a story of systematic acts of concealment that reaches from small-town police departments to the Ohio Attorney General’s office. Quinlan is in the middle of a conspiracy that has turned police chiefs into criminals, prosecutors into unwitting accomplices, and mayors into legal scapegoats for violations of constitutional rights and laws they have no knowledge is occurring under their noses.

The light switch theory

To understand how Ohio arrived at this moment, Ohioans must first understand what can be described as the ‘Light Switch Theory’ of police authority. In most professions, certification lapses are administrative inconveniences. A late license renewal for a barber means a fine, perhaps a temporary closure. The same for a real estate or insurance agent. But for police officers, Ohio law established something far more absolute.

Ohio Revised Code 109.803 and Ohio Administrative Code 109:2-18-02 are binary: on or off, certified or not. There is no grace period, no administrative leeway, no dimmer switch. The statute reads:

(A) Every appointing authority shall require each of its appointed peace officers and troopers to complete up to twenty-four hours of continuing professional training each calendar year. (B) Effective from the date of this amendment, every peace officer and trooper must complete the required hours of continuing professional training each calendar year in order to carry a firearm while on duty and perform the functions of a peace officer or trooper.

Twenty-four hours of training per year. 8 hours of mandatory courses. 16 hours of electives chosen by the “appointing authority.” Miss the December 31st deadline, and at 12:01 AM on January 1st, the switch flips off.

The only approved extension of time is one requested of the Executive Director by the “appointing authority” no later than December 15th of each year, and only after the Executive Director gives written approval for the extension. The instructions in Section 109:2-18-06(A) of the Ohio Administrative Code are final for what occurs if these instructions are not obeyed.

“(A) Pursuant to division (B) of section 109.803 of the Revised Code, any peace officer or trooper who… fails to complete and report continuing professional training… shall cease carrying a firearm and shall cease performing the functions of a peace officer or trooper until such time as evidence of compliance is filed with and approved by the executive director.”

The consequences should be immediate and obvious in the statutory instructions to all Ohio peace officers. An uncertified officer cannot legally perform any law enforcement function the minute their certification lapses. For every minute afterwards, every arrest becomes a kidnapping or false imprisonment. Every search becomes an unlawful trespass. Every moment of carrying a firearm becomes a felony, particularly when their use of a firearms ends in a death. That’s when the death penalty provisions of 18 USC 241 and 242 are triggered. Every access of the Law Enforcement Automated Data System (LEADS) or National Crime Information Center (NCIC) federal criminal databases is a federal crime under 18 U.S.C. § 1030.

But here’s the problem. The only people who know the switch has flipped off are the officer, their conceal-minded police chief, and the conceal-minded state bureaucrats employed at OPOTA. The mayor and civil service commission who appoints municipal peace officers? Kept in the dark. The prosecutor who puts the peace officer on the witness stand? Uninformed. The judge who signs the arrest warrant based on the uncertified peace officer’s affidavit? Ignorant.

This information blackout isn’t an accident. It’s the system working exactly as designed by the errant public employees it’s supposed to regulate.

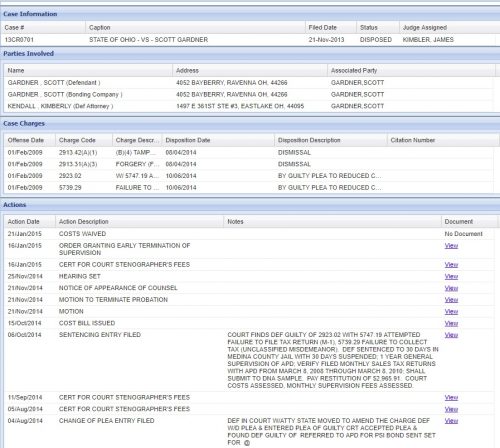

Scott Gardner offers an extreme example of OPOTA dereliction

If there is a patient zero for Ohio’s officer in “cease function” epidemic, it is Scott Gardner. I first encountered Gardner in 2006, when I was serving as East Cleveland’s mayor. Gardner, then a patrol officer, was suspended twice by me for insubordination. I refused to promote him to sergeant after learning he was running a private security company with off-duty employees he was giving checks from a bank account with insufficient funds.

By December 2013, I was out of office when Gardner was indicted on felony charges in Medina County. Before that case could proceed, he was indicted in Cuyahoga County in January 2014 on separate felony charges. Both relating to financial and tax crimes.

What should have followed was straightforward. Pursuant to R.C. 737.052 and R.C. 737.162, Gardner was automatically terminated by law after pleading his felony charges to misdemeanors. R.C. 109.77(E) instructed OPOTA officials not to give him peace officer credentials. More critically, R.C. 2929.43(D) provided instructions for the sentencing judge to snatch his OPOTA certifications.

Gardner negotiated exactly two such plea deals in 2014, reducing his felony charges to misdemeanors. His OPOTA certificate should have been surrendered at the moment the plea was accepted. It wasn’t.

Gardner kept his badge. He kept it throughout 2014, 2015 and into 2016 when Norton was replaced by then Council Vice President Brandon King in December 2016. King went a step further and promoted Gardner to lieutenant, captain, and then chief of police for the next four years. All his promotions were without civil service tests and after state laws prohibited Gardner from even thinking about discharging law enforcement duties.

Attorney General Richard DeWine let Gardner investigate a police killing

In November 2012, East Cleveland police officers engaged in a high-speed pursuit of Timothy Russell and Malissa Williams. The chase ended in a hail of 137 bullets fired by 13 Cleveland police officers, killing both occupants. The case prompted an investigation by the Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation (BCI). East Cleveland police, including Gardner, participated in then-Ohio Attorney General DeWine’s investigation.

According to OPOTA records I reviewed, Gardner had failed to take mandated annual training courses from 2009 until 2013. He was operating as an uncertified officer—a law enforcement officer impersonator—while investigating a state-sanctioned killing. Both BCI and OPOTA operate under the same roof under the Ohio Attorney General’s supervision. One arm was collaborating with a private citizen impersonating a peace officer his office’s training arm knew to be uncertified.

Gardner approved his own validations after two felony convictions

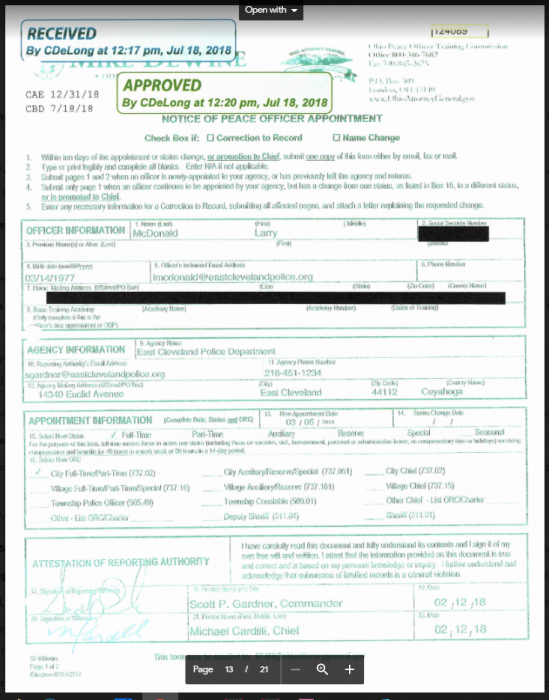

As police chief, and after pleading two felonies to misdemeanors, Gardner was responsible for signing OPOTA Form SF400s. These forms are the contractual agreements between police agencies and the state training academy. The chief’s signature on an SF400 is supposed to be a certification under penalty of law that the officers listed are properly appointed from either a civil service eligibility list or as a temporary employee under the city’s local ordinances.

Gardner, who should not have possessed an OPOTA certificate himself, was certifying the eligibility of private citizens with no civil service tests or OPOTA certifications as East Cleveland police officers, and OPOTA officials knew it. Criminally derelict OPOTA bureaucrats accepted the forms from the convicted private citizen as if they were legitimate. Gardner’s signature — despite his documented disqualifications and laws giving him no authority to sign any contractual documents for the city — ridiculously carried the same weight as that of any other chief in Ohio.

Gardner wasn’t arrested for his certification fraud, impersonation of a police officer, police chief, unlawful arrests, unlawful weapons carrying or his felonious unlawful access to NCIC, LEADS portals or the money in wages he stole from East Cleveland. He was ultimately brought down in 2023 for his third felony indictment he pleaded to a misdemeanor for unrelated financial crimes. Through it all, OPOTA never revoked his access to its portals and questioned his authority to submit other officers for certification. The state agency never notified his mayor. Never reported his violations of federal and state felony laws to any federal or state prosecutor.

Kenneth Lundy’s appointments confirm OPOTA’s incompetence

If Gardner was the blueprint for longevity in fraud, Kenneth Lundy is the blueprint for the total collapse of the civil service structure and its relationship with OPOTA pursuant to R.C. 109,76. The heading reads, “Peace officers not exempted from civil service.” The plain English language of the OPOTA law is clear.

“Nothing in sections 109.71 to 109.77 of the Revised Code shall be construed to except any peace officer, or other officer or employee from the provisions of Chapter 124. of the Revised Code.”

Lundy, a terminated ex-East Cleveland so-called captain and acting chief of police, serves as the ultimate evidence of the ludicrous nature of Ohio’s “police policing themselves.”

I discovered that OPOTA accepted the signatures and credentials of a man whose entire career was a statutory fiction. Lundy was appointed as a beat patrol commissioned officer by Norton in 2016. What followed was a vertical ascent that defied every law governing municipal corporations in Ohio. Without ever taking a single civil service promotional test mandated by R.C. 124.44, Lundy was “appointed” to Corporal, Sergeant, Commander, Lieutenant, Captain, and finally, Acting Chief of Police.

All of his ranks were fake. They were unearned by law. Furthermore, Lundy was a chronic “cease function” violator. In sworn testimony, Lundy admitted that he would ‘skim through’ mandatory OPOTA courses, completing them in minutes while receiving failing scores—some as low as 49%. Even after cheating, he could not achieve competency and still continued to investigate crimes and make arrests. He even kidnapped the mother of Ronald Newberry to force him into surrendering to him for questioning.

More disturbingly, Lundy was functionally an “illegal alien” who had overstayed his visa (characterization). This means that while he was a private citizen without legal standing to hold a public trust, he was being commissioned by the state to deprive American citizens of their liberty. Yet, OPOTA officials interacted with him as if he were a legitimate “appointing authority.”

When an uncertified, visa-overstaying, test-skipping private citizen signs an SF400 form certifying other officers, it isn’t a “portal error.” It is Falsification under R.C. 2921.13. OPOTA’s acceptance of his signature means they were validating the authority of a man who was nothing more than a civilian in a state-issued costume. Lundy’s approach to OPOTA is now being institutionalized by Thomas Quinlan’s “Training Option 3,” which criminally allows chiefs to create their own curriculum specifically designed to be “skimmed through.”

The 1,081 police OPOTA records laundering operation

On February 1, 2024, the Ohio Peace Officer Training Commission held its regular meeting in London, Ohio. In attendance were Sheriff Vernon Stanforth, Fairfield Township Police Chief Robert Chabali, Colonel Charles Jones, Lieutenant James Fitsko and Wynette Carter-Smith along with OPOTA Compliance Manager Brittany Brashears.

Brashears delivered a report that should have triggered immediate emergency action. She informed the Commission that 1,081 individual officers were non-compliant with 2023 training requirements as of 12:01 a.m., January 1, 2024.

Quinlan exceeded all statutory authority to rename the “police chiefs” whose jobs are creatures of statute as the “Agency CEO.” His act is a ludicrous corporate fiction.

There is absolutely no such statutory language designating any elected or appointed public official, particularly a chief of police or a safety director, sheriff, trooper, transit authority or park ranger chief under the “CEO” title.

Quinlan, a statutorily-untutored ex-cop who cannot amend federal, state, or local laws by memo, attempted to create a new classification of law enforcement official to bypass Ohio mayors and civil service commissions in cities as “appointing authorities.”

What Quinlan did in calling police chiefs under a mayor’s supervision an “agency CEO” was no different than acting East Cleveland Chief of Police Reginald Holcomb issuing an order that describes Todd Carroscia’s re-employment after his December 12, 2025 termination a “reassignment” to the position of “civil service sergeant” without a civil service test. There’s a mindset among police that they can add and delete language in laws to do what they want, just like they do to manipulate data in police incident reports, instead of obeying the plain language in laws that tell them what they can and cannot do.

Instead of looking to see which laws they violated when citizens complain, they go to departmental policies police chiefs created in violation of R.C. 737.06’s instructions that police chiefs work under the safety director’s rules. Because mayors across Ohio are equally as uninformed about OPOTA and civil service laws, and have not been trained to even know they exist, they can’t enforce what they don’t know and what’s been intentionally concealed from them by criminally derelict state officials in Ohio’s Attorney General’s office, now under Attorney David Yost.

Statutory illiteracy

Quinlan operates with the mindset of a career cop who has grown accustomed to reclassifying cop crimes as administrative offenses. There penchant for reclassification is among the cultural behaviors identified in the USDOJ investigation of Cleveland police during ex-President Barack Obama’s administration. Quinlan operates like the typical public employee who takes an oath of office swearing to obey and uphold constitutional mandates and laws he’s never read and mastered.

-

R.C. 109.803 & OAC 109: 2-18-06, he would know “cease function” is a statutory kill-switch.

-

R.C. 737.02, 737.05, 737.06, 737.15, 737.16, he would know he is a subordinate, and that police chiefs are authorized only to “station and transfer” officers under the rules of the Director of Public Safety (the Mayor), and have no contract or document signing authority to bind a municipal corporation.

-

R.C. 124 (Civil Service), he would know that an uncertified ghost officer falls out of civil service protection and becomes a private citizen impersonating a law enforcement officer.

-

10th Amendment & R.C. 737.11, he would know that municipal police have federal criminal law enforcement authority that is the highest in the city, and that this power is a sacred delegation of sovereign authority, not a “gym class” elective. He would know they need far more than 740 hours of training, an amount half of what it takes to license a barber or cosmetologist.

Quinlan’s “Training Option 3” guts civilian oversight. It allows unauthorized chiefs to create their own “training” with zero OPOTA oversight. It institutionalizes the “Lundy Blueprint.”

The accountability dead zone hits the courts

The private citizen impersonating a peace officer problem should have long ago been exposed by Ohio’s criminal justice system. Instead, the courts became the final layer of concealment.

State v. Newberry

In June 2025, the 8th District Court of Appeals issued a ruling in State v. Newberry that effectively immunized prosecutors from disclosing officer certification failures. The case centered on two private citizens impersonating civil service and OPOTA certified East Cleveland peace officers, Kenneth Lundy and Joseph David Marche.

Chasing Justice activist Mariah Crenshaw discovered both Lundy and Marche had been in ‘cease function’ status while conducting criminal investigations. Kodii Gibson was a defendant in a homicide for which prosecutors were prosecuting Ronald Newberry. Gibson’s attorney used Crenshaw’s OPOTA information to seek the impeachment of Marche and Lundy, and so did Newberry.

Newberry accused his attorney, Kevin Spellacy, of defending both him in the criminal trial, and Lundy and Marche in a special docket case that challenged their OPOTA credentials. So, the disciplinary rule conflicted attorney knew the two private citizens were law enforcement impersonators.

The court held that prosecutors had no duty to disclose these failures because the information was “publicly available” at OPOTA in London, Ohio. Their trial occurred before Yost responded to public pressure and created a database making the records Quinlan’s now altering, public. Under this logic, if the government buries exculpatory evidence in an obscure database that OPOTA bureaucrats are actively “manually laundering,” the prosecutor can claim they didn’t “possess” the information.

This creates an “accountability dead zone.” The Attorney General’s office maintains the records but doesn’t share them with the appointing authorities being held locally accountable for police crimes in office and seeking to reform the lawbreaking out of their unconstitutional behavior.

Prosecutors put peace officers on the stand but don’t verify credentials. There is no judicial “bench card” from the Supreme Court of Ohio instructing the state’s more than 700 judges to validate OPOTA and civil service credentials to determine the qualifications of the officers testifying before them.

Defense attorneys don’t know to ask. And uncertified officers secure convictions that are legally void because all their invalidating information is altered by the state and withheld from the citizen they arrested.

East Cleveland’s prosecutors blocked citizen uncertification complaints

When citizens in East Cleveland attempted to use R.C. 2935.09 to file criminal affidavits against uncertified officers, they were blocked. Terminated ex-East Cleveland Law Director Willa Hemmons, a contractor working with a voided contract and her own oath issues, refused to process them. Ex-city prosecutor Heather McCollough, who prosecuted citizens for years without first taking an oath of office, declined to pursue charges. The hidden corruption in each city thwarts a system of accountability to successfully insulate itself from the people it is sworn to serve.

Disconnecting civil service by abandoning R.C. 109.76

The failure of “police policing themselves” is rooted in the systematic abandonment of the Civil Service Commission — the only body designed to act as a civilian firewall between police misconduct and public safety. In East Cleveland, terminated ex-Commission Chairwoman Phyllis Mosely did nothing to protect civil service laws, failing to schedule monthly meetings for years while police lawsuits ravaged the city’s treasury and complaints of their misconduct went unheard by her and the other commissioners.

This dereliction of duty allowed East Cleveland’s private citizen police impersonators to flourish in the dark. Pursuant to R.C. 109.76, the law is explicit: “Sections 109.71 to 109.77 of the Revised Code do not exempt a peace officer from the civil service laws or regulations.” This means that OPOTA’s training requirements under Chapter 109 are not a “get out of jail free” card for police chiefs and temporary employees impersonating those who were civil service tested to bypass the mandates of R.C. Chapter 124.

The Civil Service Commission is the body mandated to oversee the “Original Appointment” process described in R.C. 109.77. They are tasked with testing candidates and creating the eligibility list from which the Mayor — the only legal Appointing Authority in a municipal corporation or charter city — may hire. They are the statutory recipients of citizen complaints against classified civil service workers and, under the linear structure of Ohio law, the Commission is the final voice on a peace officer’s employment eligibility.

The Lawful Linear Process vs. The Quinlan Loop

The real statutory process is designed to be a transparent, corrective machine under the control of three entities as training laws applied to municipal corporations.

OPOTC (State): Under R.C. 109.73, the Commission sets the minimum standards for training and curriculum.

The Appointing Authority (Mayor). As the executive head of a municipal police department pursuant to R.C. 737.02, and as an advisor to the Civil Service Commission about the city’s employment needs, the Mayor as the appointing authority and ultimate manager of the police department, should be selecting the 16 hours of elective training. This selection should be based on local policing flaws identified by Law Directors, Prosecutors, and Judges who evaluate and rule on the legal defects and peace officer violations of laws found in incident reports about their interactions with the public, and who are actively defending the city against police misconduct state and federal court complaints.

More specifically, Ohio is a “home rule” state with constitution that grants voters in municipal corporations the authority to enact their own charters and ordinances. East Cleveland’s charter, pursuant to section 113(A), gives the mayor appointment authority for all administrative employees. The mayor has dually served as director of public safety since the late Mayor Darryl E. Pittman’s January 1, 1986 swearing-in as the city’s first mayor since 1918.

The Civil Service Commission. Per R.C. 124.40, the commission audits the roster to ensure every officer is legally commissioned and trained. They establish the testing necessary to “cure” defects the Mayor has discovered in bad policing practices and lawsuits, ensuring that “original appointments” and “promotions” (governed by R.C. 124.44) are never handed to uncertified impersonators.

Quinlan has effectively lobotomized this system. By dealing only with his fake and legally unauthorized “Agency CEOs” (Chiefs), he has bypassed the reporting requirements of R.C. 109.761. He has cut the Mayor, the Director of Public Safety, and the Civil Service Commission out of the loop, illegally handing their sovereign power to their subordinates without their knowledge. If the General Manager or Board of Commissioners of a transit authority appoints a chief of police, they are the appointing authority who should be notified when their appointee’s law enforcement certification expires.

By allowing chiefs to self-certify training through “Training Option 3,” Quinlan is replacing a transparent, corrective machine with a “closed loop” conspiracy. He’s designing a system to protect the “Brotherhood” in the union over the Bill of Rights. He’s institutionalizing the practice of ensuring that no Mayor or Civil Service Commission ever sees the data that would prove their “chief” is actually a private citizen in a stolen uniform like Michael Cardilli, Gardner and Lundy.

East Cleveland’s $100 million receivership catastrophe

East Cleveland now faces financial ruin. The city stares down civil rights claims totaling between $75 million and $100 million. This is not bad luck. It is arithmetic.

Over 24 police officers were indicted and convicted since 2020. That doesn’t include the more than 12 other cops indicted and convicted between 2006 and 2020. Recalled ex- East Cleveland Mayor Gary A. Norton, Jr. didn’t know enough about OPOTA to know he was appointing a peace officer who’d taken no training when he gave Cardilli control of the police department after ex-chief of police Ralph Spotts.

Every arrest by a private citizen impersonating a certified peace officer is a constitutional violation. Every search is an unlawful trespass. Every moment they spent carrying a firearm was potentially a felony. Each is a potential federal lawsuit under 42 U.S.C. 1983.

They couldn’t enter a public safety vehicle, access a Mobile Display Terminal, be given an NCIC/LEADS user ID, operate emergency lights, pursue any vehicle, ask any person for a driver’s license and insurance, or ask them to step out of the vehicle. All these illegal acts were concealed from the arrested person by the officer, the police department’s supervising and command staff, prosecutors, law directors and the city’s municipal court judge. Since in East Cleveland the mayor, law director, prosecutors and judge knew, all were involved in an organizational conspiracy against rights.

The cruel irony is that the same Attorney General’s office that failed to enforce certification requirements through OPOTA, may now oversee East Cleveland’s financial collapse via state receivership. They created the liability. Now they will manage the consequences of their own misconduct. It’s more than an irony it’s insane.

The federal reckoning

Ohio officials are not just violating administrative law and Quinlan can’t edit and delete information in peace officer training records to retroactively conceal evidence of the federal crimes they committed against Ohio citizens.

-

18 U.S.C. 4 (Misprision of Felony): Every official who had knowledge of 1,081 uncertified officers accessing federal databases and concealed it has committed a crime.

-

18 U.S.C. 241-242 (Conspiracy Against Rights – Color of Law): The systematic use of private citizens impersonating peace officers to make arrests and testify is a textbook conspiracy to deprive citizens of constitutional rights.

Quinlan’s operational thinking is reflective of the mental midget consciousness among federal, state, county and municipal officials who read no laws to discharge the duties of public offices controlled by the laws they’ve not read. He has turned a state agency into a sanctuary for uncertified law enforcement impersonators.

Quinlan has replaced the Ohio Revised Code with his own “memos,” attempting to exercise a power to “suspend laws” that Article 1, Section 18 of the Ohio Constitution reserves solely for the General Assembly. The language of the constitutional amendment Quinlan operates like he’s never read is as simple as the “cease function” instructions.

“No power of suspending laws shall ever be exercised, except by the general assembly.”

Ohio’s choice

Ohio’s certification system was built on a simple premise: police authority must be earned annually, and when training stops, authority must stop immediately and absolutely. It’s no different than turning off a light switch from light to dark or vice versa.

Quinlan’s Training Option 3 is not reform. It is the institutionalization of fraud. It is the concealment of crimes from the public, and an alteration of a well-thought-out state law whose only amendment should include a section with new language identifying the felonies offenders are committing when they continue to exercise law enforcement authority in cease function or access the state’s OPOTA portal to enter false information.

Ohio faces a choice. It can continue the concealment, or it can enforce the law. It can revoke Quinlan’s “Track 3,” return curriculum control to the civilian-majority that includes mayors, law directors, prosecutors, judges and the Civil Service Commission, and refer the 1,081 ghost officers — along with Quinlan, Brashears and other conceal minded state and local officials who protected them — to federal authorities.

The badge is either a symbol of statutory compliance or it is a costume. In Ohio today, we cannot be sure which. And that uncertainty isn’t just dangerous. It is criminal.